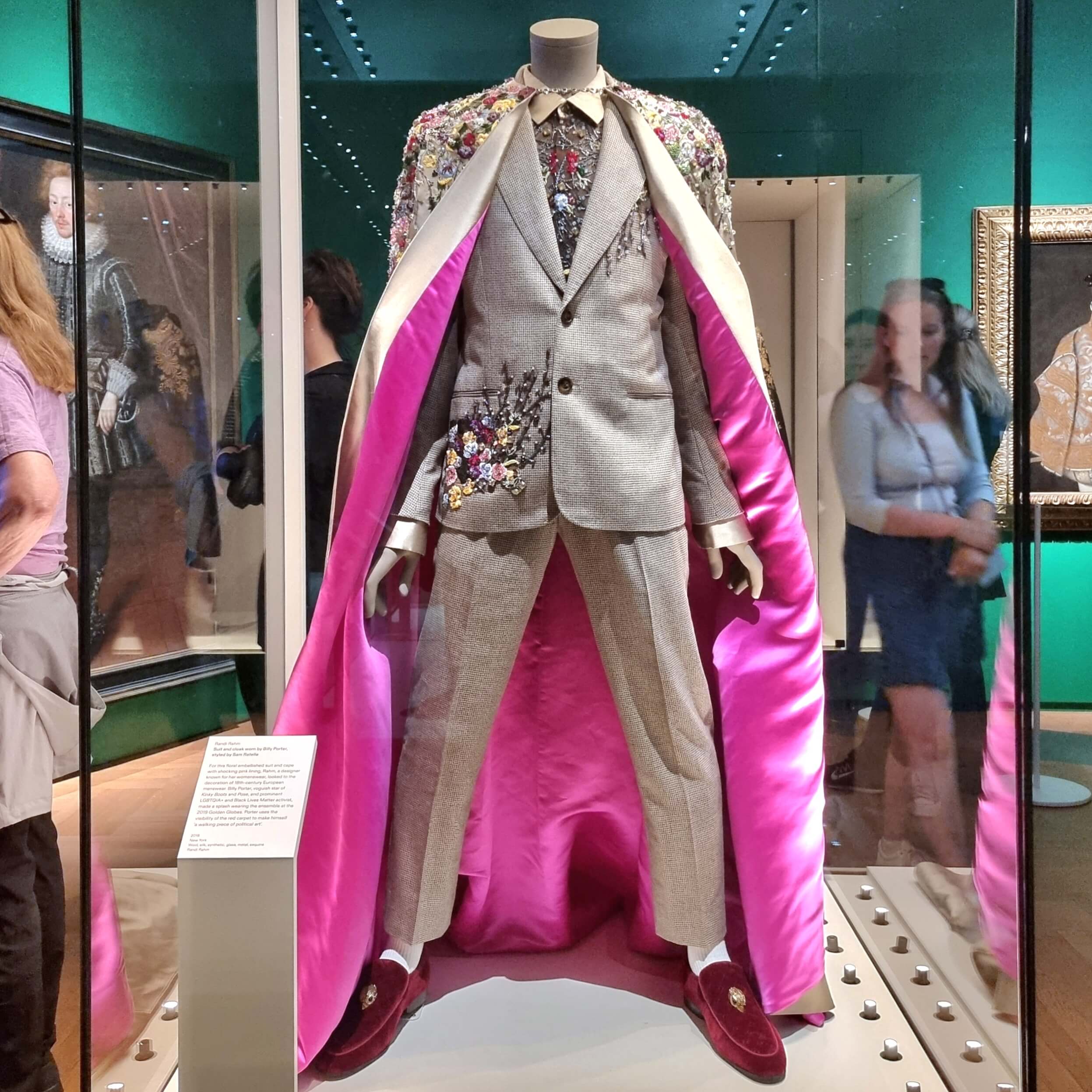

What comes to our minds when thinking “art of menswear”? Probably a suit, probably black, probably well cut. But I for myself I‘d like you to think of more than that! Think of Louis, the 14th. Think of Prince. Of George Brummel, the first dandy. Think of Billy Porter, currently one of the most exciting stars on the red carpets. Think of James Dean and Richard Gere. And of Harry Styles. All of these fashion icons prove: Men’s fashion has always been fabulous, intriguing AND extraordinary. No matter if you think of the lavishness of Baroque attire or the minimal elegance of an Armani suit – men’s fashion has always been as exciting and as versatile as women’s fashion.

Celebrating Men’s Apparel

“Fashioning Masculinities. The Art of Menswear” at the V&A Museum offers a true celebration of men’s apparel through the centuries. And this all while promising to focus on (contemporary) designers who were and are unpicking menswear “at its seams”. Walking through the exhibition one must ask oneself: Is it really only “currently”, that designers are redefining men’s fashion? And what parts of the established male fashion are currently unpicked? Quickly one must face: Men’s fashion has for a long time been so much more than a black suit and a tie, leaving today’s “Queerness” a little insufficient as a keyword. But let’s start at the beginning!

Un-, Over- and Redressed

The exhibition at the V&A Museum is divided into three sections: The first part is focusing on undergarments and the (in)visible male body (“Undressed”), the second is celebrating the “outrageously dressed” gentleman (“Overdressed”) and the last is pointing out the so-called “monochrome man” (“Redressed”).

Fashion without any boundaries

Each hall offers a feast of fashion but also loads of very diverse other exhibits: Paintings, drawings, prints, sculptures as well as objects of the applied arts (loads of extraordinary accessories!), videos showing dance performances and films and photography (Calvin Klein ads!) are draped around the exhibited clothes – not taking care of any of the established boundaries of art disciplines. This pretty simple but even in our days still courageous curatorial decision makes it super easy to enjoy fashion history as well as contextualize clothing – you literally dive into one fashion chapter after the other.

The quintessence: Clothes make the man.

“Vestis virum facit.” Clothes make the man – a proverb still pretty common nowadays was coined by no other than Erasmus in 1500, as the V&A’s catalogue states. Yes, in 1500 already. No matter if you agree or disagree that clothes make or break a man, clothes have always been playing an important role in how men (and women of course) wanted to be perceived. Clothes have always been and will always be playing an important role in social distinction. And while the goals of dressing well might have been similar for all (display of power, wealth, beauty, authority, knowledge, the membership or distinction of a social group etc.) the rules of the fashion game have always been different for men and women. Women’s Fashion has (almost) always been about adorning and decorating its wearers lavishly with all kinds of fabrics, colors, patterns and cuts whereas men’s fashion changed dramatically around 1800.

For the love of DETAIL

But no matter what era we focus on, the art of menswear has always had very precise – written and unwritten – rules to follow. Regardless if you look at the super baroque or rather minimal decades a great amount of detail was always put into the fabrics, the cuts, the patterns as well as the accessories of a (noble) man’s fashion. And for a long time these rules have been making the man – and still are nowadays.

The glory of ‘classically’ male codes

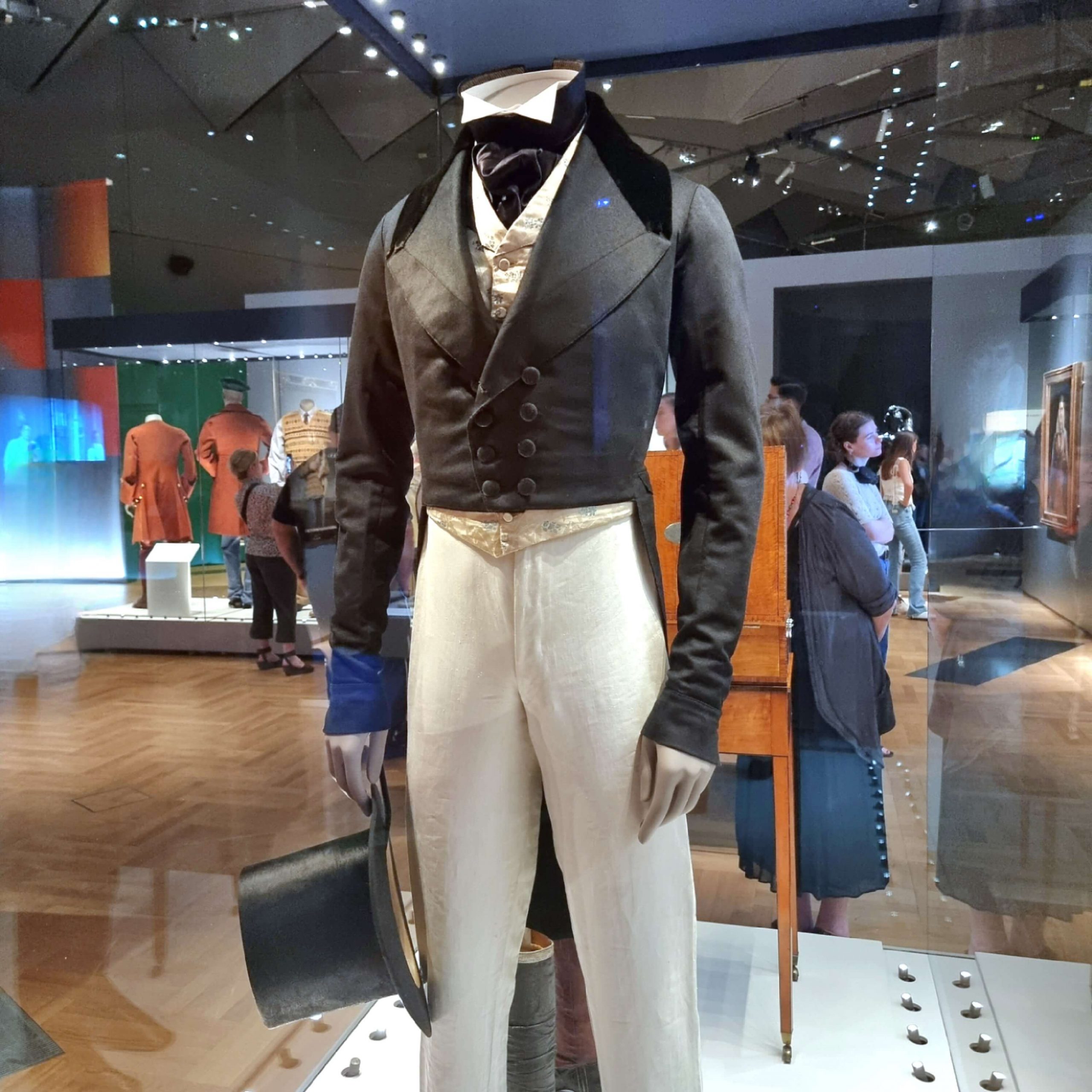

As mentioned before men’s fashion has abruptly made a shift to a darker color palette, simple cuts and the suit around 1800, leaving all kinds of bold patterns, colors and decorations aside (although black as a color did appear every now and then since the Renaissance as well). No matter if it’s the fashion influence of Napoleon and the French Revolution (and the glorifying depictions of its soldiers) or George Brummel, the first dandy, or later Charles Baudelaire, who somehow positively lamented about the black suits and dark frock coats – all of these protagonists and their influence were proof of the new fashions and their impact in the streets as well as on their contemporaries.

A modern man

The fact, that the “Modern Man” was dressed in a monochrome outfit, where symmetry, repetition as well as the lack of decoration were leading ‘motifs’, somehow appeared pretty logical for the writers of the first half of the 19th century. No matter if it was the contemporary architecture, the literary ennui or melancholy or industrialism in general (thinking of London particularly!) – all these aspects of contemporary life were parallelized to the fashions of these days. And what started as the thoughtfulness and melancholy described by Baudelaire became the morbidity and depravity of Huysmans’ works and Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray during the last decades of the century.

Roaring 60s & 70s

It was only at the end of the 1960’s, that men’s color palette began to loosen and to brighten up (Talking about revolutions!), the 7os then added their disco and glam rock effect. But black (and dark) colors continued on its road to success – no matter if you look at the 80s (Richard Gere in Gigolo wearing Armani is EVERYTHING), the 90s and the first decades of the 21st century – men’s mainstream fashion is still pretty monochrome, pretty minimal and maybe even a little boring.

Now or never? About the queerness of men’s fashion history

Between 1500 and 1800 we see loads of similar design approaches when looking at men and women. Bold reds, pinks, blues, greens as well as radiant patterns and prints were common for both genders. Also: Men’s fashion was everything but as minimal as after 1800. Loads of playful ruffles, bows and ribbons adorned the (noble) men during these centuries. All these design decisions were used to display wealth, power and – of course – good looks. But the subsequent question is: Was the image of men less masculine until 1800 than after? Or to put it into contemporary words: Was men’s fashion until 1800 “queer”? Is a Baroque gentlemen’s outfit as ‘queer’ as a Harris Reed outfit from 2017? Well, I will have to disappoint loads of the voices of the LGBTQI+-movement by answering ALL these questions with a humble but firm NO. Of course not.

Despite of what we might easily assume from our contemporary perspective all the pinks, the ruffles and the abundancy were not supposed to feminize men. Men didn’t dress like this in order to appear less masculine or more feminine. A silk suit from the 18th century was an expression of male power and wealth just as the lavish looks of Louis the 14th were supposed to make the king appear more masculine and subsequently more powerful.

But the conclusion of the exhibition’s concept is – I fear – just trying to state that. The curators stressed in several interviews, that they wanted to show the long history of gender non-conformity through men’s fashion as well as celebrate its contemporary visibility.

But the thing is: The art of menswear until 1800 was not gender-nonconformist. It was an established system of fashion codes, that played by its own rules, that were similar to women’s fashion. But it was not nonconformist, since the conformity, the curators refer to, was established only from 1800 on. Masculinity was displayed via lots of lavish clothes – but this approach was not nonconformist. Neither back then nor from our perspective.

Until 1800 ‘masculinity’ – in all its traditional understanding – was expressed through totally different ways than a James Bond or Richard Gere would do. Baroque men were not queer, they were expressing their masculinity via different visuals than the so-called “modern man”. This is why curatorial questions of when something was menswear and when it wasn’t for me are the wrong questions. The right question must be the following: What is and what was considered and worn as menswear? Because as the exhibition perfectly illustrates: The boundaries of menswear, that we have in our minds, are relatively young and have in fact not even existed for a long time. Thus one cannot talk about the “long history of gender non-conformity”. Until 1800 there was no such gender-conformity – men and women dressed alike when it came to the main visual decisions.

I do of course understand the will of the exhibition makers to dock on to current discussions and the social discourse of our Zeitgeist. But I do feel that imposing such a big topic as “Queerness” on to centuries and centuries of fashion history with such a lightness feels too easy. Because what would this thread of thought mean? That all men, who ever dressed in pink, were queer? Patriarchy has been firmly in society’s saddle throughout the last centuries – no matter if men wore pink or not. The men of the Renaissance were not queer just because they loved to wear all-over patterns. A Gucci look by Sandro Michele might be inspired by historical fashion and be using colors, prints and flowers of past colorful centuries for its contemporary male clients – but that same look probably is not made for men, who could be compared to the historical wearers of those inspirations.

That current designers are blurring the boundaries between gender normative clothing is an overly present tendency – but it’s also the result of sociological developments. The visual language of fashion back in 1500 and nowadays may LOOK similarly gender-bending but they ARE NOT coming from the same sociological background. A Renaissance duke was (usually) not queer whereas a client of Michele’s Gucci is likely to be.