Peggy Guggenheim is considered an emancipated woman with character and vision, a legend in the world and history of modern art. But who was she really? Her AUTOBIOGRAPHY suggests: Perhaps Guggenheim and her art collection just HAPPENED to be fabulous?

An OASIS of modern ART

Peggy Guggenheim’s museum seems like a fairy tale: Housed in the middle of Venice in a PALAZZO, it looks like an oasis of modern art with its Picassos, Mirós and Ernsts. And its founder also seems like THE muse, icon and patron of modernism. Her ICONIC NETWORK of literati and artists as well as her eccentric vita do not promise little in this respect.

Off to the LIFE of the individualist GUGGENHEIM

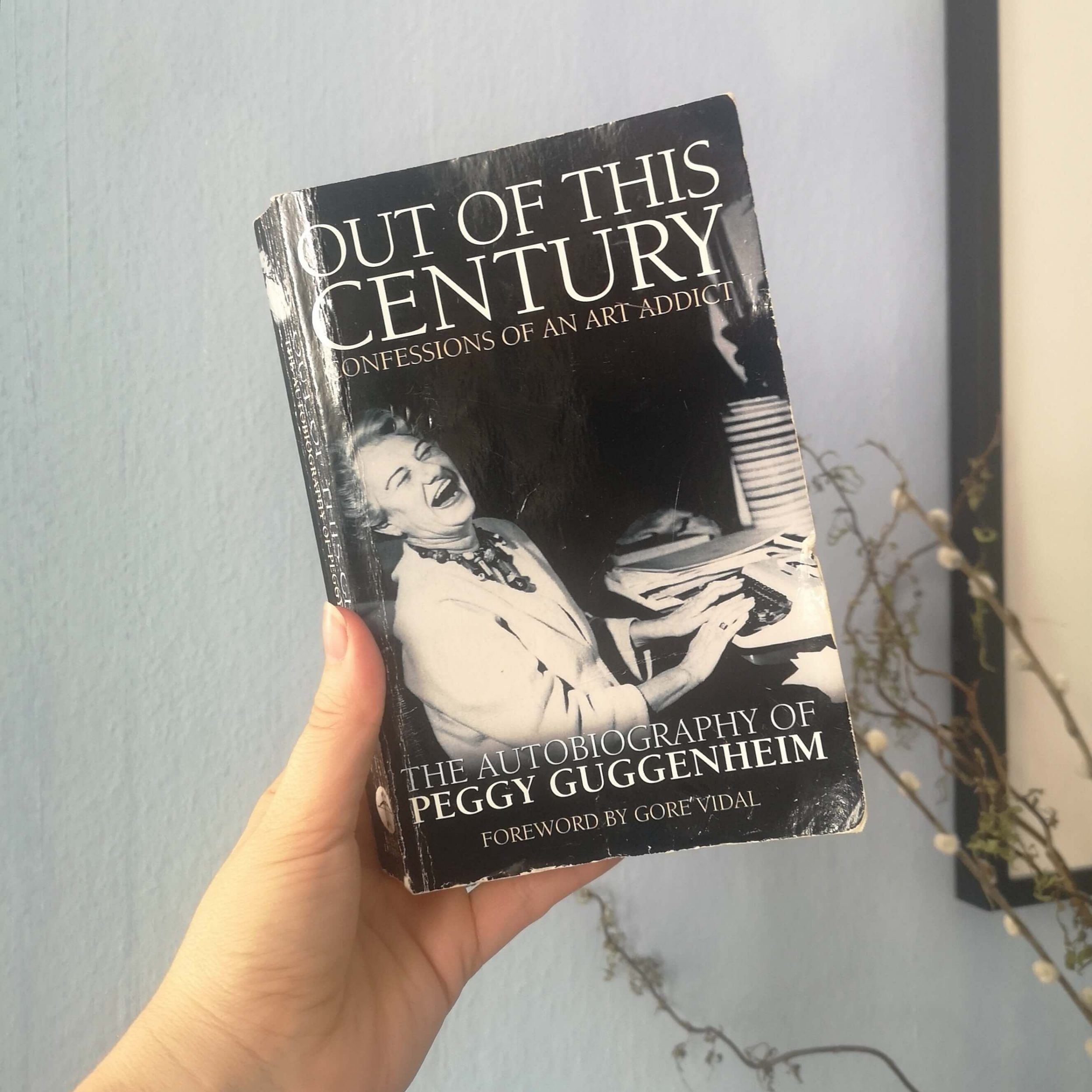

Her art museum and her history draw you in like a maelstrom. And you don’t leave without the desire to pick up at least one biography of Guggenheim to learn more about her eventful life. I bought on the spot the autobiography Out of this Century. Confessions of an Art Addict and thought: what she has to tell about herself, THAT is the most interesting thing. Someone who gathered so many fabulous people around her can only have been fabulous, right? Well, we’ll get to my optimism here – but first, back to the start: my visit to Peggy’s art museum.

Free fall into the WONDERLAND of MODERNITY

To get from St. Mark’s Square to Peggy’s Museum you have to take the BOAT. Just as Alice fell into Wonderland, so you splash along even on the vaporetto to Palazzo Venier dei Leoni – accompanied by a sea breeze and the scent of salt water. You enter the museum through an inconspicuous iron gate and come first into a quiet little garden. Immediately you want to spend the whole day there – so MAGICAL is this place.

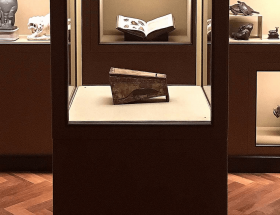

TRUE ART ICONS - and that EN MASSE

The ticket is quickly bought (together with a small, highly recommended guide for a few euros, by the way) and the tour can begin. No sooner have you entered the first room than they are already smiling at you: The works of Pablo Picasso, René Magritte and Max Ernst, of Juan Miró and Yves Tanguy – and you have arrived in the middle of FACTION LAND. Fabulous cult works await you: Magritte’s L’Empire des Lumières, Max Ernst’s La Toilette de la marièe, Dalì’s La Naissance des désirs liquides and many more.

Welcome to the INHABITED MUSEUM

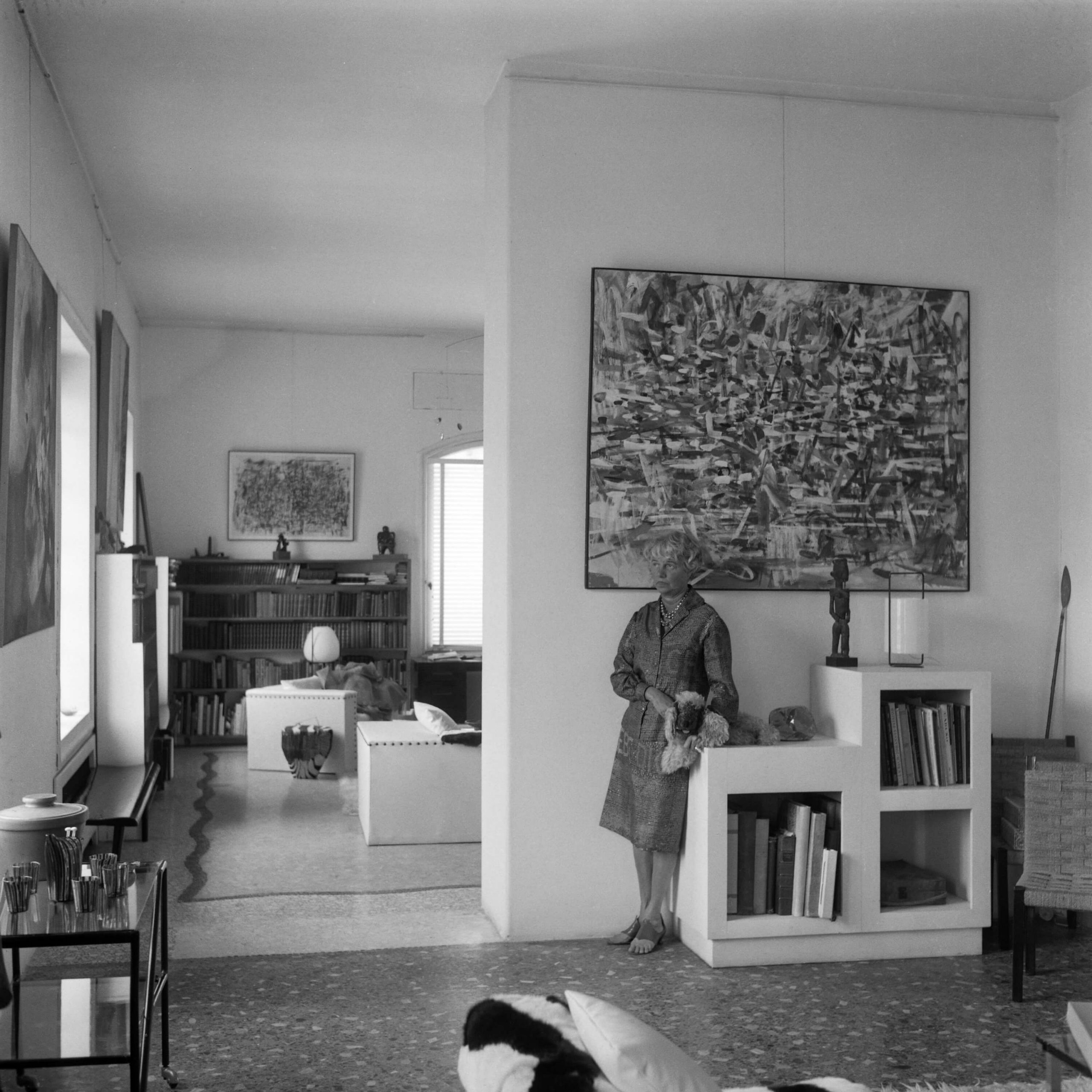

All these modern art masterpieces are housed in Peggy’s palazzo, which was once her LIVING HOUSE. Much is still there as it was then: her dining room, for example, still shows table and armchairs, dressers and other furnishings. Absolutely unique – and for me, pure FACTION.

A life in the middle of a COLLECTION

With the museum ticket you enter the past life of a fascinating personality of modern art and breathe in the scent of her EVERYDAY. In the midst of it all, the works tell of Guggenheim’s life, her encounters, and the artists she supported. Collection and life exhibit each other reciprocally: The living room atmosphere displays the works in a pleasantly unobtrusive way.

A POLLCOK in the LIVING ROOM

Pollock’s huge Dripping Alchimia, for example, appears more modest and also more intense in this setting than his works usually do in the large halls of other museums. And there’s something about a meter-sized Pollock in a living room. Few people crowd around the works at the same time – because they simply don’t have that much space. So the INTIMITY of the house has a direct effect on the intimate enjoyment of art. And lets one feel the atmosphere from the 50s, in which the “DOGARESSA”, as it was affectionately-cynically called by the Venetians, in the Palazzo fabulously.

In the EYE of the STORM of modernity

The richness of the collection quickly leads one to suspect: Peggy Guggenheim’s life must have literally taken place in the eye of the STORM OF MODERNITY. As early as the 1930s, she bought the works of Ernst, Miró, the Arps, Magritte, and many others. Her autobiography is full of great anecdotes from her large circle of friends and colleagues.

This is how she soberly describes a very fabulous scene: Alfred Barr, the founding director of New York’s MoMA, came to see her and Max Ernst one day to examine the latter’s paintings. He found the following scene: Max Ernst, in whose work and life birds played a great role, was about to catch a bird that happened to fly into the room (Evidence 1 – see below). I mean: How much FACTION fits into one scene?! Not much more than in that room with Guggenheim, Barr, Ernst and the bird.

LUST, FUN and a little MONEY

Peggy Guggenheim’s credo “Buy a picture a day” (2) is also very refreshing. Both her way of collecting and spending money seem somehow random, spontaneous and of a surprising modesty. One can’t help but be STUNned when she tells how she bought art: “The day Hitler walked into Norway, I walked into Leger’s studio and bought a wonderful 1919 painting from him for one thousand dollars. He never got over the fact that I should be buying paintings on such a day.” (3).

Her way of negotiating is also astonishing: the Delauney couple wanted to sell her a painting for 80,000 francs. She rejected this as completely excessive without even thinking of negotiating. At most 10,000 francs would have been an appropriate price in her eyes. When the Delauneys bombarded her with calls and messages, she said:” Finally I got so bored that I offered to buy it for 40,000 francs.” (4).

A MODEST fortune

Peggy’s surname suggests a great wealth and accordingly nods knowingly as soon as one reads about her sporty handling of money. After all, if you have money, you can throw it around. She was heiress to the Guggenheim empire: coming from a wealthy family as the niece of Solomon R. Guggenheim, however, she was not particularly generous.

As a young collector of contemporary art with an unconventional, bohemian lifestyle, she was considered an outsider in the family. She accepted this role with a wave of her hand and distanced herself resolutely from the New York upper class. Her financial resources were thus available, but they were not endless. Nevertheless, Guggenheim spent her money with both hands: For example, she voluntarily paid generous alimony to her 1st husband Laurence Vail and his wife – to name just one example from her autobiography.

The collecting LIONESS

Peggy Guggenheim is one of THE patrons of modernism – without her DRIVE, many masterpieces and artists would undoubtedly have had a different fate. She collected works of the avant-garde early on, often causing more established collectors to shake their heads. Even in the 1940s, her taste was considered avant-garde at best, and simply bad at worst: during World War II, the Louvre still did not consider her paintings worthy of protection and would not give her one square meter of one of its warehouses (5). She, on the other hand, defended her collection like a lioness and took many a risk to save it through the war. Her taste was GENIAL and her willpower unseen.

A ROLE MODEL for emancipated women?

Peggy Guggenheim was a dazzling collector. But was she also the emancipated woman she is often described as? Well, this keyword inevitably brings up SUSPICION. Guggenheim makes one thing clear in the 378 pages of her autobiography: Her life did not follow art. Rather, it followed her loves & affairs. She was in sexual relationships with many of her acquaintances and business partners, which – as she herself recounts – influenced many of her decisions in a very arbitrary way. Only casually – almost by accident – many of the works came into her art collection.

Peggy's decisions: ALWAYS RESTLESS

One cannot help but be amazed when reading Guggenheim’s own words and seeing how she took which step in her life. Often she followed only the whims of her men and rarely decided on her own initiative. I would hardly call her an emancipated woman with regard to that emotional and sometimes childish behavior. More like an eternal teenager who jumps from one drama to the next.

Peggy, Max and Leonora

An example: Max Ernst was still chasing his partner Leonora Carrington for ages, while he was already in a relationship with Peggy Guggenheim. Peggy, on the other hand, tried to keep him with her, to finally convince him of herself as a partner and to save him for the USA. When he left her again at short notice, she formulated the following plan: she would like to drop everything for a British man she had recently met. This also applied, by the way, to her children, with whom she was waiting for the eagerly awaited rescue flight in Marseille. The goal: to accept a “war job” in Great Britain and run away with the aforementioned gentleman (6).

Shortly thereafter, Max returned to Peggy after all, and they were able to flee Europe. An anecdote that leaves one speechless: Again, their lives happen to take not one turn but another, probably happier one. And that is only one of countless episodes she gives to the best.

To JUDGE or to CONDEMN?

Please do not misunderstand: Neither do I want to pillory the liberal woman that Peggy Guggenheim was. Quite the contrary: her so-called “unsteady” lifestyle undoubtedly testifies to a certain emancipation from her family, her New York roots, and many social conventions of her time.

Nor do I usually consider the number of love lines relevant to the assessment of a life’s work. It is just that in this case Peggy Guggenheim herself puts her life in the light of “love”, (as she calls it herself in numerous interviews), so that her life’s work cannot be described and judged without her autobiography. And one simply cannot avoid denying her many of the myths surrounding her emancipation. After all, she tells us herself what and who she was. I certainly don’t want to condemn her for this, but I do judge her life’s work in this light.

Peggy and other WOMEN

It should also not go unmentioned that Peggy Guggenheim generally did not think much of other (married) women. She repeatedly denied their importance or positive influence: “I think, most artists are better without their wives. And also this BONMOT comes from her: “I don’t like women very much, and usually prefer to be with homosexuals, if not with men”. She continues like this: “She (Nellie van Doesburg, the widow of artist Theo van Doesburg) dressed carefully, looked very attractive but made up too much. Because of her excessive vitality even I envied her.” (7).

Doesn’t sound like a woman who stood up for other women or their emancipation. Not to mention, she speaks about those women whose men she seduced with an intangible mix of feigned concern and obvious callousness. One inevitably wonders: is this a bad JEST or did she really believe that she didn’t want to make anyone “unhappy”?!

Ironic MOTHERHOOD

Her treatment of her children is also neither particularly loving nor consistent. For example, she offered her unborn child to the couple whose husband was the father of her child when his wife had a miscarriage at the same time. She describes the situation to LAPIDAR: “The irony of the situation was that they wanted a child. I offered mine to Llewellyn, but he refused on the grounds that he could make a lot more.” (8) No more words are needed.

An Autobiography as a DIME NOVEL

The sobering conclusion after about 378 pages: What is supposed to be an authentic autobiography sounds in many cases like a dime novel full of steep punchlines and interpersonal drama. The only thing is: it is not a ROMAN, it is the narrative of the main character in the flesh.

I actually wanted to get to the truth of Peggy Guggenheim. What I discovered was a passionate collector, but not an emancipated woman of vision. Page after page she surprised me with her random decisions, questionable opinions and ATTITUDES. What should be considered a fabulous life’s work is exposed by the leading lady herself as the result of ephemeral emotions and casual ACCIDENTS.

Peggy's collection: ACCIDENTALLY FABULOUS

I would love to describe Peggy Guggenheim’s life’s work as a glamorous SYMBIOSIS of her vision, her emancipated character, and her unerring sense of art. To sum up, I have to say: in a way, it is. It just has an exuberant flavor of WILLFULNESS and ACCIDENT. Because through all their personal entanglements, their collection and their museum are one thing above all: accidentally fabulous.

REFERENCES

(1) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 259, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(2) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 209, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(3) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 218, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(4) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 225, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(5) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 219, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(6) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 235, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(7) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 200, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.

(8) Out of this century. Confessions of an Art Addict, Peggy Guggenheim, Page 195, 1979 first publication, 2005 Edition, André Deutsch, Carlton Publishing Group, London, Copyright (c) Peggy Guggenheim 1946, 1960, 1979, Forword (c) Gore Vidal, 1979, ‘Venice’ (c) Ugo Mursia Editore 1962.